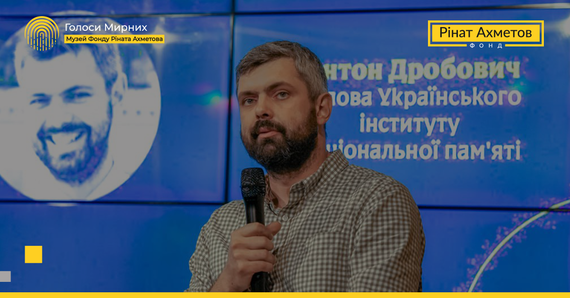

"Memory is a field for justice": an interview with Anton Drobovych, Head of the Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance, as part of the VOICES Exhibition of The Museum of Civilian Voices by Rinat Akhmetov Foundation

A public interview with Anton Drobovych, a Ukrainian public and state figure, expert in communications, education and culture, and head of the Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance, took place in Kyiv. The event was held as part of the VOICES Exhibition of The Museum of Civilian Voices by Rinat Akhmetov Foundation. The conversation was moderated by Anastasiia Platonova, cultural critic and curator.

For all countries with a totalitarian chapter in their history, setting up a memory policy is an asterisked task. After all, it is not only about preserving but also about restoring socially significant information.

"Totalitarian regimes and empires destroy archives, ban memoirs, and kill people who can tell important stories. In other words, they erase the field - you will have nothing to remember. It can reach the point of absurdity when a family dies during the Holodomor, and their only child, who miraculously managed to save his or her life, knows nothing about the fate of their relatives and eventually becomes an employee of a repressive body that protects that criminal regime," said Anton Drobovych.

The remembrance policy in Ukraine did not begin to take shape immediately after independence. Today, the expert sees three challenges in this area.

"The first is to set up a living ecosystem of memory. We are currently working on the Law on the Principles of National Memory. Its task is to make visible and give recognition from the state to the key actors - the academic environment, the third sector, experts, museum workers, archivists, etc.", says Mr Drobovych.

The second challenge is memorialisation during the Great War itself. Society demands this, but the state has an important role to play in ensuring it.

"We have incredibly strong projects, such as The Museum of Civilian Voices or this VOICES Exhibition, which show that such living memory is important to many people today. However, we will only believe that we have a memory policy among the state's priorities when we see the material embodiment of this policy. We are talking about various objects, from the Holodomor Museum to the National Military Memorial Cemetery and the proper arrangement of places of memory in the regions," explains Anton Drobovych.

The third point touches on transitional justice. According to Anton, even during the war, it is important to determine the legal liability of those who help the enemy administration in the temporarily occupied territories.

"We have to be clear: there will be responsibility for such participation. This is a matter not only of jurisprudence but also of national memory because it is about the right to the truth. It is important to record what happened: it may happen that only newspaper publications or testimonies in the Civilian Voices or the archive of oral histories of the Institute of National Remembrance will be the only form of justice actually achieved," the expert says.

Anton Drobovych adds that no national system in the world has ever ensured justice exclusively through the courts within the criminal law framework. And often, memory remains almost the only realistic field of justice after a war.

The public interviews are part of The Museum of Civilian Voices series of cultural events aimed at preserving the memory of the war. Follow the announcements of the events on the social media of Rinat Akhmetov Foundation and the Museum's website: https://civilvoicesmuseum.org