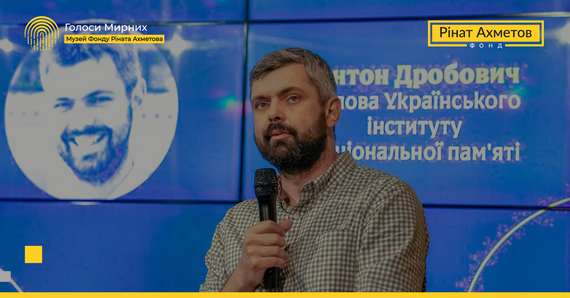

‘Memory is a field for justice’: an interview with Anton Drobovych, Head of the Institute of National Memory, for the Museum of Civilian Voices by Rinat Akhmetov Foundation

A public interview with Anton Drobovych, a Ukrainian public and state figure, expert in communications, education and culture, and head of the Ukrainian Institute of National Memory, was held live as part of VOICES, a three-month exhibition of the Museum of Civilian Voices by Rinat Akhmetov Foundation. The publication Istorychna Pravda released a shortened version of the conversation.

It can be found here: https://bit.ly/3TMAZtP

The Foundation has prepared a full video interview with Anton Drobovych, moderated by Anastasiia Platonova, a cultural critic and curator: https://youtu.be/-QUti8wnns4

During the interview, the expert noted that in countries that have emerged from totalitarian rule, special institutions are created to restore national memory. After becoming an independent state in the 1990s, Ukraine became one of the countries with the same task, but failed to fully fulfil it.

‘The situation changed after the Revolution of Dignity, when we realised that memory was being used against us as a weapon, influencing the mass consciousness. The state recognised the importance of this issue, began to create memorial institutions and support them, although not enough. The invasion showed that the Russians are working in this area: they forbid us to talk about human rights, to study our own history, and justify the communist totalitarian regime. In 2014, we began to counteract more actively, and the apotheosis was 2022 and February 24, after which it became clear that we would have to act even faster,' the expert emphasised.

They also talked about the gradual realisation by Ukrainian society after 2014 of its role in interacting with the state authorities - not separating from the authorities, but engaging with them and responding to Russian aggression.

‘Society has become more involved in these processes, and the topic has become more widely discussed. And then the realities of the war came to the scene: coffins from the frontline, which changed the situation significantly. Crimea, Donetsk and Luhansk residents were among the first to feel the seriousness of this part. This showed that national memory and the politics of memory are no less important than the economy or security. It turned out that Russians are primarily concerned with education, the language of education, culture, museums, and content. Authorities, NGOs, academic institutions, and those people who were the first to feel what all this was leading to, began to mobilise and focus on preserving memory,’ explains Anton Drobovych.

According to the expert, there is an incredibly large demand for memorialisation in Ukraine today, and our country is doing something that other countries have not done.

‘We are now unique in the world in that we are engaged in memorialisation during the war, discussing transitional justice during the war, holding exhibitions during the war, and all these people are still alive! This is almost unprecedented. This is a new approach to commemoration. It's not a certainty that it will work, but we have a great chance. We are alive and continue to fight, so we must use every opportunity to ensure that our memory and justice find their place in the future,’ Anton Drobovych emphasises.

The museum collects and stores the world's largest collection of first-hand accounts of the war in Ukraine - more than 120,000 stories. The VOICES exhibition, which was visited by over 5,000 people, was held at Kyiv City History Museum and was based on the stories collected by the Museum of Civilian Voices.

Follow the announcements of events in the social networks of Rinat Akhmetov Foundation and on the Museum of Civilian Voices' portal https://civilvoicesmuseum.org/